Last fall, social media buzzed with Elizabeth Gilbert’s talk on creativity. Gilbert, who has led workshops on finding your passion, presented the flipside at Oprah’s event. While she herself has followed her passion all her life, she understands that not everyone is cut out of the same cloth. She divided people into jackhammers—those who doggedly pursue a dream—and hummingbirds—people who explore many interests.

I realized instantly which group I’m in. I have little patience for people who don’t know what they want to do with their lives, students who dither over majors, or anyone who doesn’t single-mindedly follow a childhood calling. I’m tedious to be around.

If someone asks me how to become a children’s book writer, I’ll reply, “How bad do you want this?” and then I’ll scare the pants off that person by telling them to forget about going to the movies or messing around with friends or taking vacations that have nothing to do with work or belonging to organizations or even having coffee.

Once I was asked to give a writing workshop on a cruise ship. When I laid out the schedule, the director said, “People can’t do all this. They’ll want to take Pilates and go shopping.” “Pilates!” I shot back. “They’ll have work to do!” And so it’s gone my entire life–everyone else out shopping and taking Pilates while I did my work.

I mentioned the jackhammer-hummingbird discussion to my husband. “Why is it I’ve only ever been able to do one thing?” I asked. He said he actually admired my ability to stay with a passion sparked when I was seven. I’ve never quit, he said, not when I was sick, not when people I loved were dying, especially not when my career sank, more than once. “You don’t know the word ‘no,’” he said and I was stunned. It was true.

But I hate the comparison to a jackhammer with its implications of being single-minded, noisy, intrusive, capable only of tearing up pavement. Who wouldn’t want to be a hummingbird, a delightful fairy-like creature? Hummingbirds zip from one interesting flower to the next, pollinating joy wherever they go.

In my life, I’ve known lots of hummingbirds but only one other jackhammer.

When my cousin David was ten, he went with my aunt to the drugstore. David slipped behind the counter to watch Dr. Hook fill his mother’s prescription. From that day on, David wanted to be a pharmacist. He attended college and pharmacy school. After graduation he worked for pharmacies before opening his own. David had other interests, but never wavered from the dream that struck him at age ten.

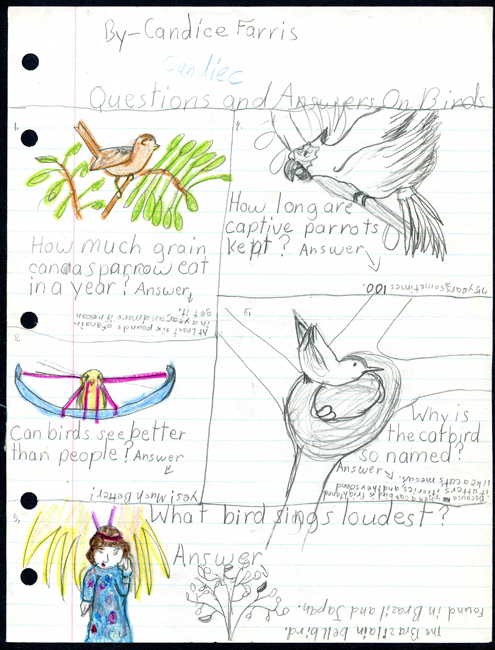

I was around ten, too, when I began sorting out my own interests: watching birds, drawing, reading, writing stories. Yet I loved writing the most.

The only time my love of writing flagged was in seventh grade. Everything flagged in seventh grade. I went from a small rural elementary school to a big intermediate school. I weighed 72 pounds. I had bad sinuses. The bravado I’d stockpiled when I was ten and eleven dissipated in that new place where I had to change classes, open a locker, and, worst of all, change out in gym class.

My favorite class was three-hour ESG (English, Social Studies, and Guidance), though you’d never know it by my grades: Cs and Ds in Social Studies, and Bs in English. I adored Miss Dail. She was young, just out of teacher’s college, and pretty. She wore fashionable A-line skirts, Peter Pan collar blouses, circle pins, loafers.

I so wanted her to like me, but she didn’t because I was skinny and adenoidal and crooked-toothed and wore hand-me-downs. Miss Dail warmed to the “Annandale” girls, the cute, bubbly ones who’d traveled and were already interested in boys and clothes and make-up. I was still playing with Ellsworth and watching birds.

I tried to get her to notice me by doing long extra-credit reports on subjects like Australia and honeybees, researching in the library before school started, copying them in my neatest handwriting, including pictures, and putting them in store-bought covers.

I turned the reports in along with regular homework. And heard nothing. Nothing at all. Near the end of the year we had a unit on careers. Miss Dail set up a long box with folders on various occupations. I already knew I wanted to be a writer but was sure that wouldn’t be in the box. I needed a real job. I also wanted to be a bird scientist. I rifled through the folders but couldn’t find ornithologist. I went up to Miss Dail’s desk for help.

She smelled wonderful, light and sweet, and wore a crisp Madras blouse. I told her my occupation wasn’t in the box. “What is it?” she asked. “Or-nee-thee-o-LO-gist,” I said. I could spell the word and knew what it meant but I’d never heard it said. “What?” Now she was irritated. She wanted me away from her desk, my open-mouthed breathing away from her, my pale green face out of her sight.

She took me back to the box, ripped through the remaining folders, and yanked one out. “Here,” she said. The folder was labeled Forest Ranger. So I wrote up my occupation on being a forest ranger, picturing myself on a fire tower with binoculars, scanning the sky for birds. No wonder I got Cs and Ds. Nothing about seventh grade seemed to fit me.

On the last day of school, Miss Dail joked with the cool kids as she returned papers. She handed me back my extra-credit reports without a word. There was a check mark on the covers, but no grade, no note, only the barest acknowledgement of my efforts. I felt flattened, but decided from then on I’d please myself. Watch birds, draw, read. Write.

In high school thoughts of or-nee-thee-o-LO-gy were buried under a burning desire to become a writer of children’s books. At fifteen, I started writing for publication, submitting a picture book I’d illustrated myself in red, blue, and black ink pens, and a mystery novel that was so firmly rejected, the return envelope bore tire tracks. My mother steered me into secretarial courses, hoping I’d abandon this outlandish notion.

My senior English teacher recognized my desire. After class we talked about how I’d become a writer. She treated me like a real person. (By now I weighed 98 pounds and had had my adenoids removed.) Miss Boyle lent me a new book, The French Lieutenant’s Woman. She thought I’d love it, but Fowles’ story was beyond me. I didn’t want to disappoint her so I kept the book and kept the book and kept the book until near the end of the year when she asked for it back.

That spring Miss Boyle also tried to get me a scholarship at a small college. The scholarship covered tuition but nothing else. My family had no money for room and board. I wouldn’t admit that so I told her I couldn’t see how college would bring me closer to becoming a children’s writer. Between the book and the scholarship, I’d disappointed the only teacher who’d ever shown the slightest interest in me. I would follow my own path. And Miss Boyle would have new students the next year.

One day near graduation, I sat alone in our living room. The 1970 Spring Children’s Book World had come in the Sunday Washington Post. On our scratchy harvest gold sofa, I read every book review, studied every single ad with an eye toward my future. I would do this thing, become a children’s book writer, just like all these other people who’d had books published that spring. I even picked out a publisher: Lothrop, Lee, and Shepard. They published the kind of books I wanted to write. At seventeen I was beginning to understand how to play the game, though I was barely in it.

I stumbled and made mistakes, but never, not for a second, lost sight of my goal. Even though I reached that goal ages ago, I haven’t stopped because there are more stories inside me. A lifetime of reading and writing has led my curious mind from flower to flower, knowledge that has been funneled into my work.

I dislike Elizabeth Gilbert’s divisive terms of jackhammer and hummingbirds. I don’t like being pigeon-holed in any way. I doubt anyone does.

Those things I loved when I was ten—art, reading, writing—I do them all as part of my work. Outside, birds flit by. Sometimes even hummingbirds.

7 thoughts on “Are You a Hummingbird or a Jackhammer?”

I will join you on the jackhammer side, no matter how unattractive the term. I’ve known I wanted to be a book illustrator since I was about 8-years-old. But back then, I didn’t know actual humans did that sort of thing. I was steered into graphic design by the adults in my life. It took me 12 years of that track to finally get onto the road I was always supposed to be on. I’ve just called it stubborn, like a dog with a sock. Better analogy? Although I suppose I could also qualify as a hummingbird with all the tangentially related things I also adore – writing, teaching, speaking, etc. Although, it’s all still about the books. 🙂 e

Welcome, fellow jackhammer! Sometimes it takes us a while to get on that path. I followed a few that weren’t right myself, but that’s called being in your twenties.

And we may have hummingbird tendencies, but all those tangential things are really part of The Work. Unless you quit and become a belly dancer, you’re stuck in this field, same as me. Ain’t we lucky?

I think so! 🙂 e

Oh, I fall into the jackhammer camp. When I have any “extra” time, I draw or paint or write. I have to force myself to stop working and go to bed. I don’t like the jackhammer metaphor either, it is not very appealing… Maybe squirrel. Always busy busy busy. Burying those manuscripts to dig them up later… I do know lots of hummingbirds. They flit flit and often never settle to finish things.

Yes, I recognized you as a fellow jackhammer within five minutes of meeting you. But you outclass me. I don’t have nearly your stamina! I too work all the time but watch the clock because at 9:00 I must go to bed. Which means I have no downtime. I generally work right up till that hour. I like the squirrel metaphor better!

I am four parts hummingbird, one part jackhammer. I’ve tried so many different things.

I will admit to being a distracted individual, when there are so many creative things I want to try. But I am determined to find that one thing that will leave a stamp on the planet.

Melissa, many people fall into your category. Still searching, still directed. I wouldn’t worry about it. You make art and write and take photos. Those things add up to making your mark. And if you never did another thing, those gorgeous girls will leave your stamp.