You wait years to take an important trip, saving money, carving out time from work and obligations, reading up on your destination. You finally go and see the places on your list and more besides. And then you come home, and friends and co-workers ask, “How was your vacation?” Because you know people aren’t really interested in your trip, any more than they want to see your photos, your experience gets boiled down to a few sentences: “It was great! We went to the Cotswolds, so pretty. And we saw Stonehenge, incredible!”

But that hardly scratches the surface. You were in someplace new, yet familiar. You wanted as much as you could wring out of five short days. You wanted to find the real England. And you wanted England to change you.

To find the real England you have to get off tour buses and away from tourist attractions. You have to step off Piccadilly Street in London, the shops churning with tourists. Fortnum and Mason is so ridiculously crowded, you leave without a buying a tea bag.

You zip across the street to Burlington House, built in 1670, a palace that doesn’t fit any description of a house, and enter the great front door to the Geological Society. Here you won’t find a single tourist. The foyer is hushed: a desk fashioned from slabs of British minerals manned by a receptionist. You tell her you’d like to see William Smith’s map, please. It’s not an unheard-of request. Ever since Simon Winchester wrote The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology, and revealed that William Smith’s famous map was hanging in the Geological Society, people interested in how one man mapped Deep Time through rocks and fossils manage to find their way to Burlington House.

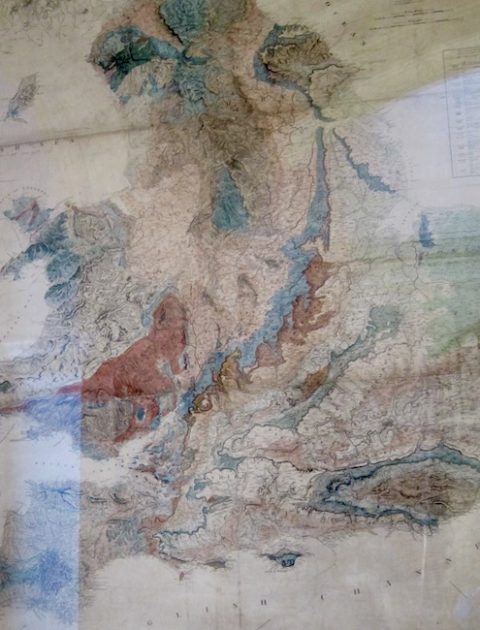

The receptionist asks you to sign in, then she opens the drapes that keeps light from fading the 200-year-old map. You stand as close as you can, letting Smith’s fine drawing guide you through England, Wales, and parts of Scotland, the watercolors as fresh as yesterday. You balance on a ledge to photograph it. A man comes down the stairs and cautions you not to slip. You tell him you came all the way from Virginia to see this map—not entirely a lie.

He offers to show you another geological map at the top of the stairs and you gaze upon it reverently. Then he asks if you’d like to see the Society’s Council Room. Of course, you do. You follow him into the room where Fellows have just had a meeting, judging from the leftover sandwiches and tea urn. The man points out a painting of scientists studying the Piltdown skull and a pair of William Smith’s chairs. Out the window you see tourists streaming into Fortnum and Mason, more tourists mingling with Londoners who weave through sidewalk throngs, Brexit crouched in the back-kitchens of their minds.

The man takes you to the bookstore-library so you can buy fossils. The harried, scattered-seeming clerk isn’t quite sure where anything is yet brings out boxes of ammonites and trilobites for you to choose—at 2£ each, a bargain—and then wraps them carefully since the fossils are traveling all the way back to Virginia, adding little description cards, and places your oversize postcards of William Smith’s map in a nice envelope, and reminds you to watch the famous Fortnum and Mason clock across the street when the bells from the same foundry as Big Ben play musical airs every fifteen minutes and on the hour the mechanical figures of Mr. Fortnum and Mr. Mason come out and nod to one another, but you’d have to stand there twenty minutes and though the librarian wouldn’t mind and you’d love to stay in that room filled with learned words and ancient stones—a haven above Piccadilly Street with its rush of red double-decker buses, black cabs, and delivery trucks—it’s time to leave.

Down the worn steps you go, one hand gliding down the smooth bannister, past the framed map made by the man who realized rocks held the secrets of the Earth and time was locked in fossils, past the receptionist who informs you that the nice man who showed you the hallowed upstairs is actually the executive director of the Geological Society, then out the door and back across Piccadilly where you forget to look up at the Fortnum and Mason clock, much less hear the airs through the traffic noise, up to Waterstone’s bookstore where you buy a nonfiction book called Pebbles on the Beach because even the smallest stones carry Deep Time.

Next you move on to the Natural History Museum in South Kensington where you view William Smith’s fossil collection, and in the museum gift shop you buy a chunk of peacock ore for 2£, pretty sure the base mineral bornite has been treated to enhance its purply-turquoise tarnish, but you think it’s pretty and want to believe the legend that says it contains properties of happiness, and when you reluctantly walk out of the museum because you have run out of time, you realize that you have found the real England after all, and that you are changed.