It has been said that a map isn’t a journey. But sometimes–especially in books–it is.

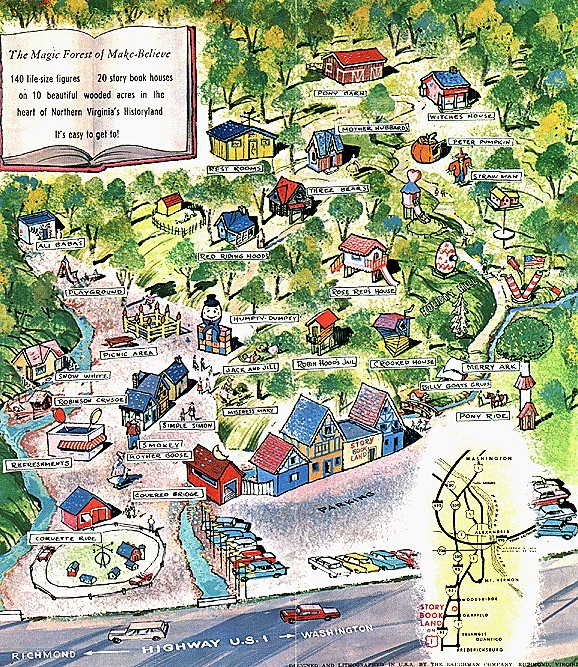

The first map I remember was flashed briefly on TV, part of a commercial for Story Book Land. It aired on “Captain Tugg,” a local kiddie program. I adored Captain Tugg, so anything he endorsed must be gold. Like the home-movie type kid shows of the 50s and 60s, Story Book Land was a family-owned amusement park. And for my ninth birthday, I was going to Story Book Land!

The day of my trip brought a family crisis. After things had settled down, we went to Story Book Land. My mother sat on a bench while I followed the colored map given at the ticket booth to Robin Hood’s Tree House and Ali Baba’s Cave. The map promised adventure, but the park itself, with its fiberglass houses and nursery rhyme figures, fell short. This may have been my earliest experience with anticipation exceeding the actual event, yet my love for maps grew out of that disappointment.

The fantasy books I read abounded with maps. The Hobbit, Watership Down, The Phantom Tollbooth, The Wizard of Oz, the Narnia books, all provided maps to help readers picture imaginary worlds. As Richard Padron says in Maps: Finding Our Place in the World, “[verbal mapping does] not have the same impact, [or] provides quite the same experience. That impact has everything to do with the seductions of seeing a world that is not our own.”

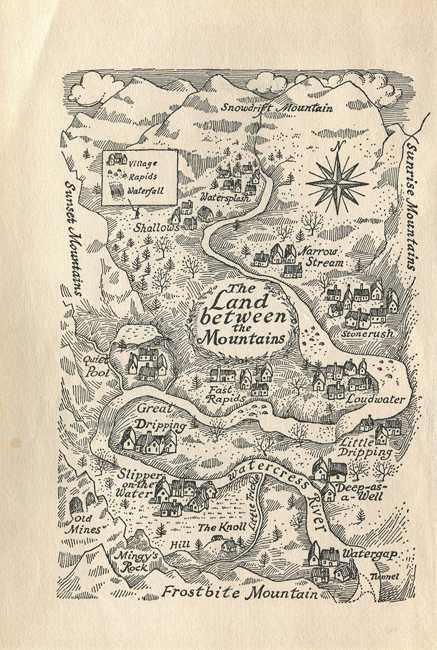

I was enchanted with the map in Carol Kendall’s The Gammage Cup. Erik Blegvad’s drawing of The Land Between the Mountains gave me a sense of the topography, essential to understanding the story. My finger traced the river tumbling from Snowdrift Mountain to the forbidding Frostbite Mountains. The river was the source of life for the tiny Minnipins. If I ever found myself in the Land Between the Mountains, something I wished for mightily, I’d easily make my way to Slipper-on-the-Water, the best of the twelve villages. The map added to my reading experience, kept me anchored in that world longer, which was fine by me. My own world was a grease spot in the road in rural Fairfax County, sadly lacking rivers and mountains, giants and tiny people.

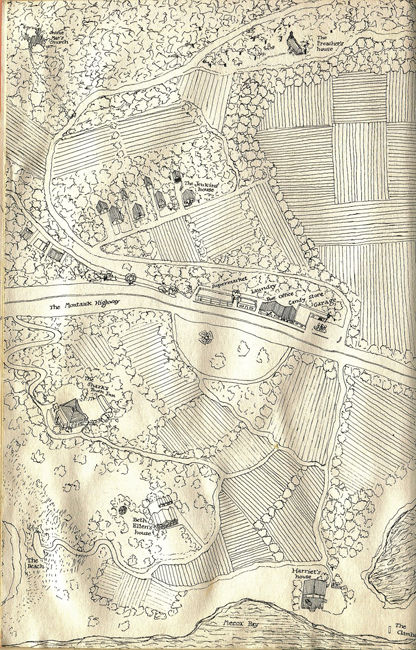

Maps in contemporary fiction serve the same purpose. When I read The Long Secret, the sequel to Harriet the Spy, I entered a place as foreign as any fantasy: the hamlet of Watermill, Long Island. It was a stretch to navigate the references of well-heeled people, such as the fact Beth Ellen’s mother was in Biarritz. Was that a mental institution, I wondered? The map showed me that rich people lived in the country, too, if only “summering.” Meticulously rendered roads, houses, shops gave me confidence I could walk down Montauk Highway to Harriet’s or Beth Ellen’s house.

In a blog post on maps in literature, Nicholas Tam says, “Fictional maps introduce the complication of having, at minimum, two layers of authorship: the layer outside the text that has the power to dictate and reshape the world, and the layer that belongs to the reality of the world. The author is in the first and the characters are in the second.”

The map by Christopher Robin in Winnie-the-Pooh, with its childlike language (“100 Aker Wood,” “Floody Place”) lets readers believe the place is real because it was drawn by a peer. Christopher Robin may be a character in the story, but he is also a kid that readers can trust. I came to Winnie-the-Pooh as an adult, yet Hundred Acre Wood seemed real (it is!). It’s safe to assume that Tam’s second layer dominates the authorship of that map.

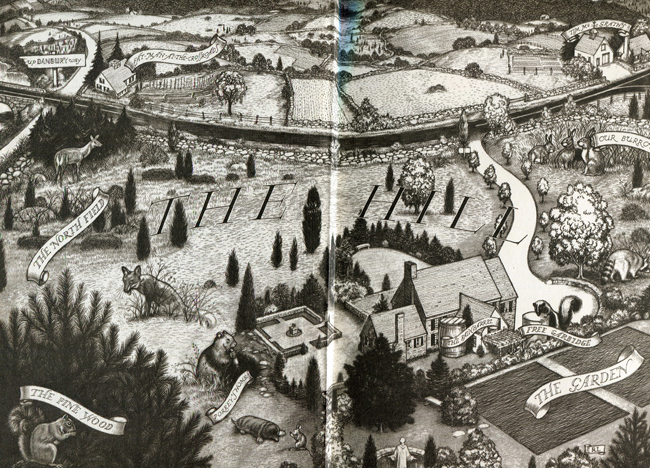

Yet authorship of a novel’s map isn’t always reliable. Look at Robert Lawson’s gorgeous end papers for Rabbit Hill. Animals are depicted bigger than the landscape and buildings, certainly not to scale, though their larger-than-life size suggests their importance against the human backdrop. To the right, “Our Burrow” indicates the rabbit narrator drew the map. But would a childlike rabbit be able to create such a lovely piece of art? It’s clear to me that the first layer—the layer outside the text dictating and reshaping the world—is the author. This doesn’t bother me one whit. If Rabbit Hill is this dazzling, I’m ready to move there.

Maps in children’s books made me notice my own surroundings. Suddenly the grease spot in the middle of Lee Highway wasn’t that boring. Houses, barns, the auto garage, the motel, all were magic landmarks that I knew by their secrets. When I began writing for publication, I set most of my stories where I grew up, carrying in my head those houses and barns, long after I left, long after the place changed drastically. Their secrets stayed with me.

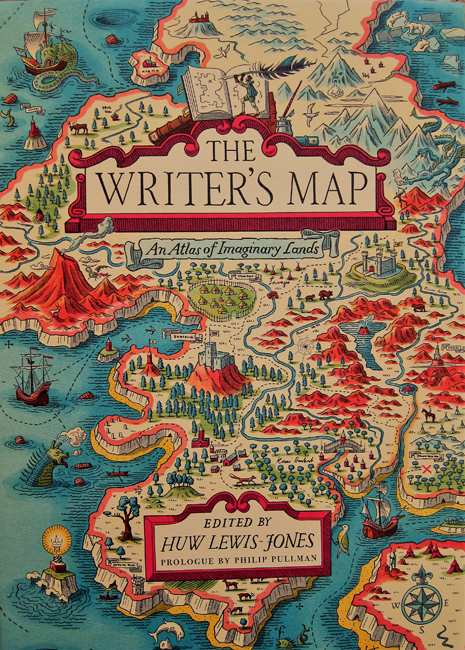

In Abi Elphinstone’s essay in The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, she too uses the map of her childhood in her books. But she goes one step further, she draws her own maps, especially on “those days when the words sit stubbornly out of reach.” She says, “I have never found myself at a loss when doodling an imagined world.”

For my new work in progress, I’ve brought out colored pencils and Micron pens. I don’t draw that well, but I know my created world won’t be made of fiberglass.

4 thoughts on “When a Map Is a Journey”

Gads – what a wonderful post! Must share… xxoo 🙂 e

Please do! In this world of GPS and Google maps, people are losing their map-reading skills. Maps are still important in books (and in real life).

Maps in books are so important to me. It’s the author offering not only proof of these worlds, but also a gift/souvenir to the reader.

I am reading Lord of the Rings and I am constantly scouring the four part maps to keep track of those silly hobbits. My only wish is that the maps were larger.

Well put, Melissa! When I only had the paperback editions of LOTR, I had to squinch to see the small map. Then I got the first slip-cased hardcover edition (in the early 70s) and the maps are fold-out. Much easier to read! I’m reading something of Tolkien’s I’ve missed–Smith of Wooton Major. Can’t believe I missed this!