The catbirds come north from Florida to our house in April. The male declared from our cherry tree that our yard was his. Pilgrim-gray, catbirds sing a very loud, varied song. They are mimics like mockingbirds and thrashers, tossing patched-together bits of other birds’ songs punctuated with a crisp bzzt. Most people prefer melodious mockingbirds, but I love the catbirds’ bright morning wake-up.

I watched them start a nest in our huge Japanese maple bush. Catbirds nest in thickets, the denser, the better. But we have outdoor cats in the neighborhood. I worried about the nest in the low shrub. I shouldn’t have. Catbirds often build a “dummy” nest to draw attention from their real nest. That one they built in the hedge up against our porch. The female ripped up our fiberglass gutter lining while the male pitched ragtime tunes.

This would be our catbird summer. I would work on creative projects and write a “heart” book while catbirds hatched and fledged close by. My new middle grade novel is out this summer, too. My first middle grade book since 2012. It even has a map! Summer was looking up. And then I read, “Not Lost in a Book: Why the ‘decline at 9’ in kids pleasure reading is getting more pronounced, year after year.” Dan Kois’s piece was published online in Slate.

The gist of the article is that kids aren’t reading for fun much anymore. There are several contributing factors. The pandemic, during which young kids learned to read by Zoom, ruined them by the time they were third, fourth, and fifth graders, those critical years to build lifelong readers. They became used to screens and less interested in books. Also, new classroom reading programs in many states emphasize short basal passages, followed by a test. There is little time for independent immersion in real books.

There’s more. Librarians and teachers are hit with book banning. Book banning isn’t new but it’s rampant now with conservative groups taking aim at children’s books. Worse, the sales of middle grade novels—the books that capture those new readers and make them forever readers—are plummeting. “Thoughtful, serious, beautiful” novels are being turned down by publishers because they won’t sell. Barnes and Noble is thinning their middle grade shelves in favor of best-sellers (I can kiss a B&N signing goodbye).

“Kids want to read a fun book. That’s what kids want today—they want to have fun.”

I pulled this quote from the article. It comes from Brenna Connor, industry expert for Circana’s BookScan. BookScan is “a data provider for the book publishing industry that compiles point of sales data for book sales.” The Circana website states they are “the leading advisor on the complexity of consumer behavior.” BookScan data “is used beyond publishing to track the psychology of the consumer in everything from food intentions to brand licensing . . .” The video shows a disembodied hand leafing through a graphic novel.

I don’t know about you, but I’d rather not have my food intentions tracked and analyzed. I could tell BookScan outright I lean toward chocolate and sugar. But Connor must be on to something because publishers are asking for short, light humorous stories that can be heavily illustrated. To me, that sounds a lot like a chapter book, not a middle grade novel, and panders to the notion that today’s kids don’t have the attention span of newborn gnat. With such fare offered, they’ll never be ready for Charlotte’s Web much less The Lord of the Rings.

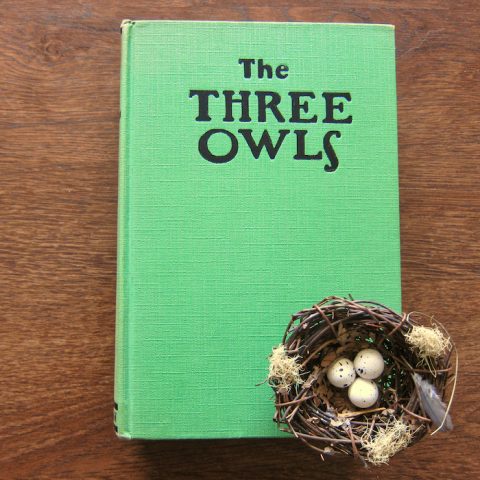

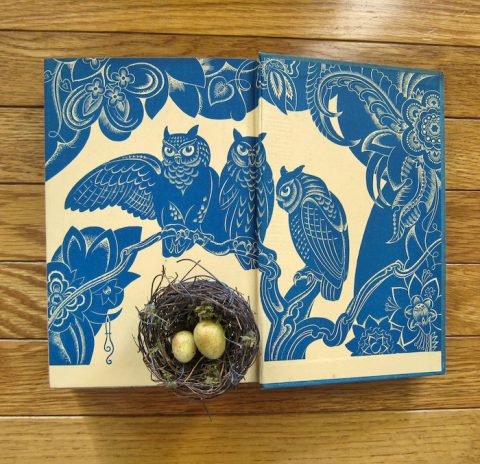

Before fixing supper, I wandered into my private library. We have books in every room, including the bathrooms, but the library is mainly books. Randomly, I pulled The Three Owls off the shelf. The 1924 book is a collection of columns by Anne Carroll Moore, head of children’s services for the New York Public Library. Moore was asked by the New York Herald Tribune to write a weekly column about children’s books. At the time, she was working at the brand-new children’s library in Westbury, New York, where the rooftop weather vane sported five metal owls. Taking inspiration from the weather vane, Moore called her column “The Three Owls.”

In the first chapter of the book, Moore explained why such a column was needed:

Promiscuous merchandising of “Juveniles” with small regard for authorship, illustration, or content has flooded the market with substitutes for children’s books in bright, meaningless cover jackets tagged with various ages of unknown and sadly neglected readers.

Nobody who knows and loves real books is ever satisfied with substitutes, and publishers’ catalogues of children’s books are beginning to indicate a highly gratifying separation of the sheep from the goats in publishing offices.

And yet, deleted, emasculated and cheaply decorated editions of well-known children’s books, and new titles of commonplace, spineless, poorly written books continue to flow in and out of reviewers’ offices every year. . .

Moore pondered the request:

Can I do it? Do I want to do it? That evening I walked down across the fields of Old Westbury to a nearly three hundred year old farm to watch the chickens go to roost. Then I walked back across the quiet old fields in the moonlight, close to the edge of a deep wood, and watched the fireflies come out in a beautiful garden known and loved by the wild birds of Long Island, who are fed and sheltered there all winter.

Then I saw that the [weather vane] owls had moved in the night. They were pointing north-northeast, and I knew, as surely as Diamond knew [from George MacDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind], that a thing had to be done when the North Wind commanded, that the reviewing of children’s books must not be delayed any longer.

Moore decided she would write weekly columns though the “books must be real books to win a place here.” To the owls on the weather vane, she said,

Three of you must fly to the woods above Peterboro to-night, and there you will find an artist painting—painting in wood blocks behind a woodpile. He wouldn’t stop painting for any human but he will for three owls who have nothing to wear. He will give you warm feathers and beautiful wings, strong beaks and sharp claws and when you fly over the little houses in those lovely woods, bring back a bit of the song of the hermit thrush that sings by the spring below Edward MacDowell’s cabin. It isn’t going to be possible to edit ‘The Three Owls’ without a new song now and then. It must be real, remember.

I walked outside on the front porch. The catbirds in the hedge by the railing had been quiet lately. I’d spent the last two weeks shooing cats and directing lawn mowers away from there. I figured the female was laying eggs by now. Not only was it quiet, but the pair had been conspicuously absent. Something was wrong. I crept over to the hedge and peered through the thorny branches. I could see the nest. There weren’t any birds in it. But something was. I parted the branches and spied a snake coiled in the nest. I could see it breathing.

No. Not in my nest! I ran to get my husband. Then I raced to the shed and grabbed a pickax. I was furious. My husband and I debated on how to approach the snake. The snake sensed the vibrations of our voices and footsteps. When I parted the branches again, it slithered like spilled mercury out of the nest and through the hedge. I grabbed the pickax to chop it to pieces.

But the snake was gone. Shaking with anger, I carefully lifted out the nest. Inside was one beautiful green-blue egg. The juvenile rat snake, about 18 inches long, had napped around it. Knowing snakes, I took the nest so it wouldn’t come back. But neither would the catbirds. I felt terrible.

That evening, I went back outside on the porch with The Three Owls. I read a review of Walter de la Mare’s Peacock Pie, a collection of poetry that “appeals to that part of a child’s nature which is not put away at maturity, but which should be lifelong.” I read about the Halloween Story Hour in Harlem. I read about Vacation Boxes from the Bookshop for Boys and Girls in Boston, packed with books about pirates and horses and boat-building, selected for each child’s current interests, and sent with them to the Berkshires, Nantucket, and Canada. I wished I was a child in 1924 listening to those stories, browsing in those libraries, having my own box of summer reading books.

I thought about the article on kids not reading in 2024 and how a one-hundred-year-old book made me feel more connected to children’s literature, my chosen field, than that online article blitzed with distracting ads and pop-up videos. I thought about the “heart” book I wanted to write and realized it would never sell. It wouldn’t be short, it wouldn’t be funny, and illustrations would be redundant.

Suddenly the female catbird lit on the railing and stared at me. The travesty of her nest washed over me. I explained to her about the snake and how it would take all her eggs. I apologized for removing the nest she’d worked so hard to build. She flitted up into the cherry tree, gave two sharp notes, and flew away. I knew the catbirds had left our yard forever. I was heartbroken.

I cried for hours. I cried because I so wanted the birds to have a successful nest, even though odds are stacked against small creatures. I cried because kids that come to my public library in the summer jump on the computers to play games or watch insipid videos, ignoring the rich adventures waiting quietly on the shelves. I cried because the field I love and have devoted nearly 60 years of my life to is in disarray and I can’t see a better outlook.

But the birds will try again, somewhere else. I have their nest, woven with fiberglass threads from our gutter and strips of plastic weed-blocker from my rose bed, and that beautiful egg. If they can go on, then so must I.

I opened The Three Owls again to an essay by Frederic Melcher, who proposed the Newbery Medal in 1922 and the Caldecott Medal in 1937. Writing in 1924, he said: “The production of a beautiful and suitable book for children gives as genuine a thrill to its publisher as it does its author, and the present high state of the production of children’s books is testimony to the real interest that is felt in all such ventures.”

With a sigh, I closed the book, longing once more to hear the bright, hopeful song of the gray catbird.

1 thought on “Catbirds, Owls, and Kids’ Books”

Well said. I’m glad my children didn’t have quite so many distractions and yes, choices in the years barely preceding the cell-phone-at-the-ready-for-all-entertainment days that followed. The library and summer reading programs were a highlight.