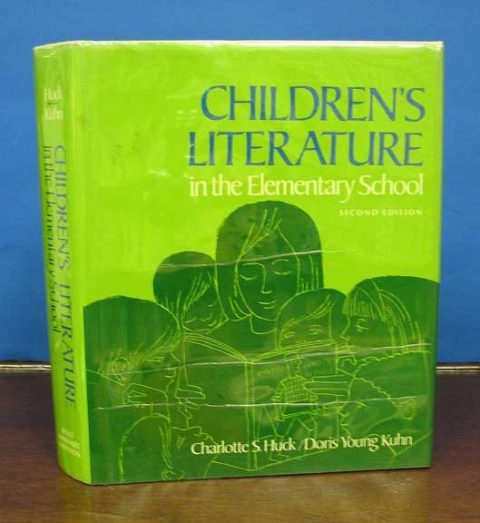

My first inkling there was a thing called children’s literature came at a yard sale. I picked up a thick green textbook, Children’s Literature in the Elementary School, by Charlotte S. Huck. I marveled at the idea that people discussed and studied the books I loved and planned to write, that children’s books were literature, like Moby Dick. I was eighteen, one month out of high school, working as a secretary. The textbook cost a dollar, steep for 1970 tag sales. I wasn’t leaving without it.

I didn’t read the textbook as much as own it. It went with me from job to job, rental to rental, representing a goal I’d reach after I was established in my real career as the next E.B. White. I was aware I’d skipped a crucial step but couldn’t afford college. Drive and desire would have to substitute for formal education. Along the way, I’d brush up on children’s literature.

The publication door didn’t open for me, but I cracked a back window. My first book, and many that followed, were paperback originals, popular fiction that kids bought with their allowance at B. Dalton or ordered from Scholastic Book Clubs. The first two published books gained me entry into the exalted Children’s Book Guild of Washington, D.C. As a guest at monthly luncheons, I was enthralled by talk of school visits, library conferences, and the easy banter of writers comfortable in the club of hardcover publishing. I loved the Guild’s fellowship but even after I became a real member, I felt second-class because my books weren’t literature.

This feeling was underscored by the Cheshire Cat, the famous children’s-only bookstore in the tony part of D.C. The Cheshire Cat was my mecca. I dropped hundreds of dollars on new books, including texts on children’s literature for my collection. But I was told I didn’t qualify for an author signing because my books weren’t for the library market. However, once a year, members of the Children’s Book Guild were invited to a reception and group signing. For those Brigadoon evenings, I bought a new outfit. My paperbacks with their photo-realistic covers (so kids would know what they were buying) seemed trifling next to weighty stacks of hardcover books with artistic dust jackets.

Eventually my books were published in hardcover: fiction, nonfiction, picture books. The paperback originals I continued to write sold in the tens of thousands and paid the bills. My husband and I moved, too far for me to drive to Guild luncheons. I fed my children’s lit fix with week-long conferences at Shenandoah University. How I loved strolling around the campus, eating in the cafeteria like a real student (Froot Loops for lunch!), mingling with teachers and librarians.

Next, I treated myself to Children’s Literature New England, an international symposium held at various New England universities. A week of heady discussions and famous speakers left me dizzy: Gregory Maguire, John Rowe Townsend, Paul and Ethel Heins. I yearned to be a smart, serious writer whose papers and speeches were published in prestigious journals. But I was still the girl from rural Willow Springs, Virginia, who never went to college. I attended CLNE for four (expensive) summers, once in England, then stopped, knowing I’d never really belong to that rarified group. Maybe if I got a degree, I’d be legitimate.

There were plenty of college programs for adults. What kept me from getting an undergraduate degree? Math. You won’t find anyone less inept with numbers. Then another back window opened. Vermont College of Fine Arts let me pursue an MFA in writing for children. I was fifty and had never stayed in a dorm. After graduating from VCFA, I was accepted in Hollins University’s graduate program in children’s literature. Now I’d be able to understand the scholarly texts in my collection! Maybe even write papers that would be published in journals!

On the very first day in my very first class, History and Criticism of Children’s Literature, a student dropped the term dialogic, referencing a text we were reading. I copied it in my notes, whispering, “Dialogic . . . what is that? Crap! I am so up the creek!” Despite my fears (and three more summers of dorm life), I felt in my element in the Children’s Literature Alcove, a room devoted to sources and books. I earned my MA by writing passionate papers on the books I loved as a child, ignoring close reading analyses and popular critical theories. Never once did I use academic jargon. No one suggested I submit my papers to journals.

I walked with my class at commencement in May 2008 and in June I was teaching in the program. I enjoyed my students, who only a few months ago had been my classmates, and my apartment (parking space, private bathroom!). As faculty, I advised thesis students, attended conferences, and listened to scholarly papers. My colleagues were brilliant. Most of my students were brilliant. I felt like an imposter. Any second someone would find out. My diplomas would turn to dust.

Where did I fit in the world of that big green textbook I picked up fifty years ago? Would I ever make my contribution to children’s literature?

This time a door opened. After I’d written several pieces for Bookology Magazine, an online publication about children’s literature. After contributing to the “Knock Knock” column, editor Vicki Palmquist asked if I’d like my own column. Yes, please! We called it “Big Green Pocketbook”, after my most successful picture book. BGP became the place where I could put my thoughts about children’s literature.

I count myself lucky to be in the company of wonderful writers, illustrators, teachers, librarians, reading specialists, and other professionals who devote their lives to creating and sharing children’s books. Bookology Magazine makes me feel real. At last, I belong.

7 thoughts on “The Big Green Textbook”

Charlotte Huck was my Children’s Lit professor at The Ohio State University as an undergrad in the 60s. I adored her. Especially when she read aloud to us. This green book and her love of literate defined my passion for teaching, reading, writing and art. I’ve never “belonged” anywhere but in her class and within the pages of her book I found a place where things ran true to me. I still clutch both to my heart.

Sarah, I’m so moved by your response. How lucky you were to have known Charlotte and studied with her. I know exactly how you feel even though I never shared your experience. I have a huge library of books on children’s literature, some I still can’t understand. I relate to my Golden Books, the only books I had as a child. I suppose that’s where things ring true to me.

Much love . . .

Candice, The irony is that being friends and colleagues with YOU is part of what makes me feel like I belong in the world of children’s lit. So, there’s that! xxxooo e

You’re no longer that outsider status. You’re “in” now. And you’ve worked hard to get there. You’ve earned it.

xxxooo

I too have a simpler way of looking at the books I read. I sometimes wonder about the deep analyses created by others – How did they make that leap? Is that how deeply the author was actually thinking when they wrote their stories?

Melissa: I remember discussions in my critical classes in which everyone was fishing for deeper meanings in a–to me–straightforward passages. Finally, I spoke up as a writer, not a student. I said, “Because that’s all she could think of to write!”