In late September of 2018, I stood at the corner of 37th and Madison Avenue in New York City and gazed longingly at the elegant pink marble building that housed J.P. Morgan’s library, now the Morgan Library and Museum. I’m willing it to be January 25, 2019, the opening of the Morgan’s exhibit: “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth” exhibit. But I must wait.

I only travel to New York every three or four years, but I’ll come back to see this exhibit, even if I have to crawl. You see, I read The Lord of the Rings when I was thirteen. Afterward, I moved to Middle-earth and stayed the next eleven years. I drew pictures of hobbits and Gandalf and thumbed to page 126 in The Return of the King again and again to experience the most thrilling sentence in English literature—“Rohan had come at last.”

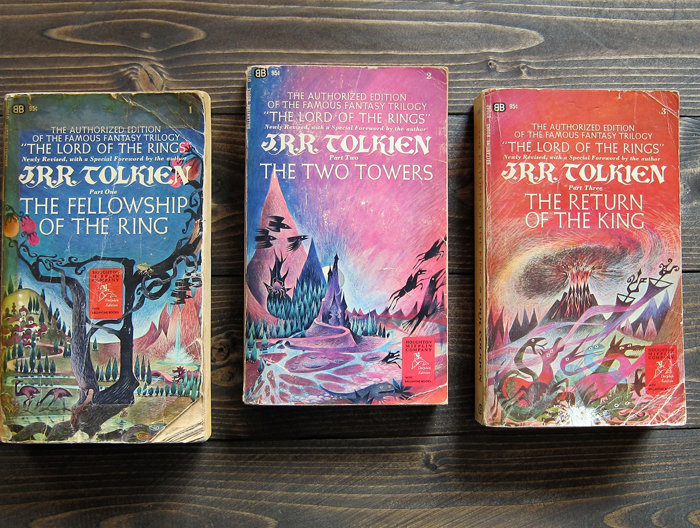

I have several copies, including the 70s hardcover editions in slipcase, a heavy one-volume edition I read with the book propped on a pillow, and the movie-based versions. But the books I prize most are the 1967 Ballantine mass market paperback editions with Barbara Remington’s strange cover art. Originally, I checked out each volume from the library in hardcover, read it in school, in bed, in the car, as I walked, and returned it feverishly praying the next volume would be on the shelves. When I found the paperbacks in the first bookstore in Fairfax, I nearly fainted. My very own Lord of the Rings!

The fantasy made me want to tell everyone about the trilogy and at the same time tell no one. I wanted Tolkien’s masterpiece all to myself. This is a common notion among bibliophiles. In her memoir, My Life with Bob: Flawed Heroine Keeps Book of Books, Plot Ensues, Pamela Paul writes, “I considered certain books mine, and the idea that other people liked them and thought of them as theirs felt like an intrusion.” I also wanted more Lord of the Rings, but there wasn’t any. And The Hobbit didn’t cut it.

Those paperbacks went everywhere with me, house to house, state to state. In each move, things got left behind: yearbooks, my high school diploma, my mother’s kitchen table, the dress I was married in (not a wedding dress). But never Lord of the Rings.

On my last morning in New York, I wandered around the Upper West Side with children walking to the various P.S.’s and private schools I’d read and wondered about in books like Harriet the Spy. They walked with parents and nannies and baby brothers. They walked with friends and dogs and siblings on scooters. These three children stayed ahead of me. At first I thought the boy was staring at a device. But he was reading a book! He wasn’t catching up on homework, he turned the pages too fervently. His book was so engrossing, he couldn’t put it down.

In an essay in the October 2018 Harper’s, William Gass writes of his beloved Treasure Island, a cheap paperback that saw him through “high school miseries,” went with him to college, and was stowed in his Navy duffel during WWII. Despite the yellowed, brittle pages, Gass admits, “That book and I loved each other.” He doesn’t mean the text, but the physical book. Books on a screen, he maintains, “have no materiality . . . off the screen they do not exist . . . they do not wait to be reseen, reread; they only wait to be remade, relit.” I can’t imagine squinting at The Lord of the Rings on a Kindle, trying to find page 126 in the third volume, unable to lose myself in Remington’s cover art that forms a triptych when the individual books are lined up.

As a child in the 80s, Pamela Paul sought vintage “yellow back” Nancy Drews (the ones I read as a child). The original 30s blue spine books were too old, and the new paperbacks were “loathsome.” She preferred the 60s editions with their interior drawings and “broody cover paintings.” The quality of the paper, the binding glue, the end papers made the book a treasured object, “the vase as much a pleasure as the flowers.”

The books we keep forever are the ones we owned back when buying a book was a big deal. When we made the effort to track down special editions. When we would walk and read because the book would not leave our hands. I hope the book that New York schoolboy was reading changed his life, that it was his, and that he would keep it forever, no matter where he went.

After high school, I got a job as a secretary. I hung a poster of Remington’s Lord of the Rings cover art over my desk. (Clearly, I was not your average secretary). At the age of 24, I decided it was time to leave Middle-earth. In March of this year–I’m counting the days–I’ll return to New York to see Tolkien’s original papers and drawings and maps. I’ve already bought my “train reading” book, A Hobbit, A Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered, Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918, by Joseph Loconte.

Meanwhile, I’ll re-read my Ballantine paperbacks. The door to Middle-earth is always open.

6 thoughts on “The Books We Keep Forever”

I love this. One of my students who went to Oxford with me brought her mother’s Ballantyne edition of The Hobbit. In Tolkien’s Collected letters there is a letter to his editor at Unwin in which he ridicules these covers as an example of American vulgarity. He hated them, but he was a control freak who wanted to have control over every aspect of his texts. I got to see this exhibit last time I took students to Oxford, and it is WONDERFUL. He was such a doodler. I loved seeing the doodles he made while doing crosswords.

I’ve read that he hated Remington’s art. He liked Pauline’s and that’s about it, unless, as you said, it was his own. I have the catalog book on this exhibit and also the book about Tolkien as an illustrator. I leaf through these books at the end of the day to relax and marvel at his genius. This vulgar American cannot wait to get to that exhibit!

Although I have never been a Tolkien fan, I attended the Tolkien exhibit at the Bodleian Library in October. It was quite something to see the artwork and fan mail! I know you will get more out of it than I did, but I’m glad I had the opportunity!

Somehow seeing the exhibit in Oxford would be more enchanting than seeing it in New York. But I’m thrilled to see it at all. Maybe you’ll be tempted to go back to Tolkien’s work?

I wish I could go with you! Although, I think this will be a solitary religious experience for you – not meant to be shared. Write about it again once you’ve seen it, please!

xxoo

e

Yes, it will be a solitary trip–not even my husband is going. And I will write about it!